Visible Absence – Photos and Postcards from the Collection of William A. Christian, Jr.

Open to the public:

March 24, 2017 – Extended: May 28, 2017

weekdays: 11am – 7pm

weekends: 11am - 7pm

Mai Manó House is closed on holidays.

Curator: Gabriella Csizek, Nóra Vörös

The new exhibition of Mai Mano House presents a selection from the photo and postcard collection of the American cultural anthropologist William A. Christian, Jr., who currently lives in Spain. Christian’s personal collection is closely related to his research area examining the relationship of religious people with the manifestations of unearthly, supernatural powers, i.e., is with the events of religious miracles.

The miraculous images of various saints, their sculptures coming to life, the locations of magical healing venues, and the visions related to the saints span through the history of Christian culture. Together with the cult surrounding these occurrences, they served as themes for painting and sculpture in the Middles Ages and the Baroque Period especially. However, the visual layout of Baroque visions does not only survive through the modern copies of icons enjoying prominent adoration or the postcards commemorating cultic places, but it has also been imbued into the visual world of family photos and mass-produced, non-religious-themed commercial postcards of the early 20th century.

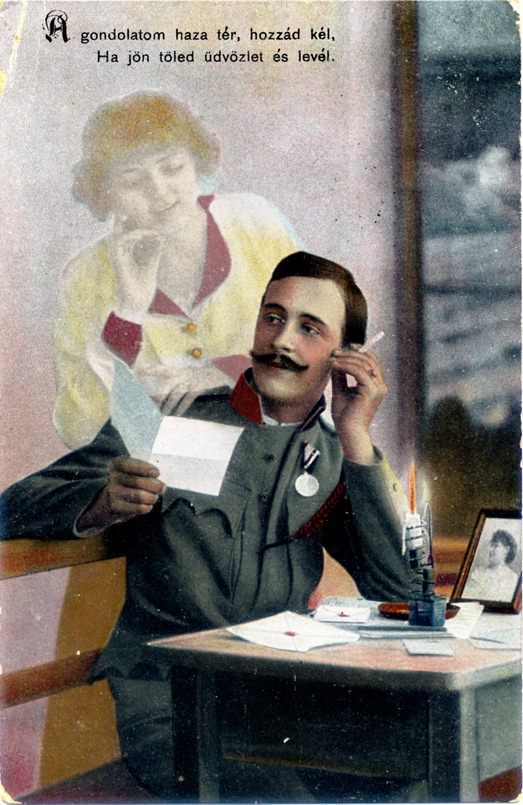

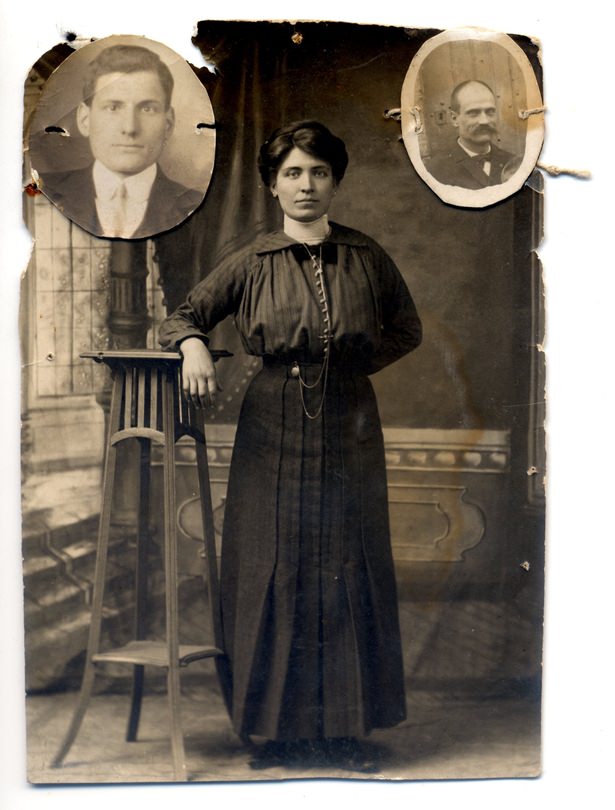

During World War I, postcards and photographs were the links between absent relatives and loved ones all over Europe, carrying not only written but visual messages as well: The figure of the absentee was either summoned by using the technique of photomontage, or by simple cutting, displaying as such the absence ‒ and presence ‒ of the person gone. These illustrated and written notes became devoutly guarded treasures of people ‒ the parents, children, loved ones, and siblings, ‒ who got separated by war or, for ever, by death.

The exhibition features a selection of these at times spooky, at other times cloying images which, in all cases, are interwoven with personal stories and history.

Nóra Vörös, associate curator of the exhibition

Pictures are a way for us to see and remember others when they are not present. Combining pictures is a way to remember people as together. A simple procedure to bring people together symbolically is to move their images—whether statues, paintings, or photographs—together. We commonly place combinations of photos around us, on the bedroom wall, the refrigerator door, the bulletin board, the desktop, the mirror rim.

For photographers at the turn of the twentieth century, a further simple step was a photo collage, taking a picture of photographs arranged together, or pasting one picture beside another as a way to visually unite a family whose members are separated physically or by death. We see examples here from Spain, France, and Japan.

But the darkroom provided more dramatic solutions for uniting the absent and the present. Photography from the start was put to use to capture the ineffable, to show apparitions of divine beings, of the dead visiting the living, or of spirit guides in séances. And local photographers attempted to meet the demands of their clients to show in pictures more than those who are present. We see a rural family in the French Alps arranging its women in a kind of visual family tree and inserting a dead girl in an extended family portrait of affection and grief.

The rise of commercial photo postcards and their massive industrial production in Vienna, Berlin, Dresden, Leipzig, and Paris provided the public and local studio photographers with a wide variety of techniques for combining the absent and present. These visual experiments took place at the same time as cinematographers like Georges Méliès were inventing ways to produce similar effects in moving pictures and exhibiting sequences of religious or phantasmagoric apparitions with great commercial success.

On commercial postcards, the more common ways of “seeing” the absent included thinking of them when writing or receiving a letter, being lost in thought with hand to cheek, staring off into the distance, looking at a photograph, dreaming, or praying. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century other inventions were making it easier to be in contact with those distant, especially the telegraph and the telephone. Commercial postcards joining absent persons sometimes included these means of communication.

Imitating the commercial postcards, studio photographers in the first decade of the twentieth century settled especially on a particular spatial arrangement, to indicate absent loved ones. They placed the persons present on a lower level and those absent on a higher level and skewed to one side. This arrangement followed conventions from religious art of humans having visions of saints, and depictions of persons beseeching religious images in votive paintings. (It reflected the relative positions of devotees in regard to images on church altars, and notions about the location of heaven in the sky.)

Conscripts provided a ready market for commercial montages (the soldier or sailor thinking of his loved one, or vice-versa) and also for personalized versions, which became a specialty of photographers in towns with large military or naval bases.

With World War I, the separation of millions of families from soldiers in imminent risk of death sharpened the need for joining the absent with the present. Across Europe there was a massive expansion of commercial postcards, and a popularization of combined images in personal photographs. While two level montages were the most common, another procedure, especially favored in Germany and the Tyrol, was the insertion of the absent person into a family group by rephotographing collages.

When a soldier came home on leave he could have a real family photo taken, one in which he could be present. The people in each of these photographs know it could be the last one. Prisoners of war could not come home on leave. But correspondence with them, facilitated through Switzerland, enabled the sending of photographs, their conversion by home or prison camp photographers into combined portraits, and their return in the new form.

German-occupied Belgium had an unusual density of combined images. Many Belgian families were separated in the war, for hundreds of thousands of soldiers and male civilians crossed into France and neutral Netherlands, or across the English Channel to England. Captured Belgian solders were sent to camps in Germany or to work on German farms. Direct mail service between occupied Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands facilitated the exchange of photographs that recomposed couples and families.

Art historians have lately paid attention to the power of images. The virtual reunion in photographs of those present with those absent showed the power of this relatively new medium to capture and express affection. The images in this exhibit, many of them reminiscent of holy cards, remind us how much photographs had by the First World War become iconic in nature, complementing or replacing religious statues or pictures on the commode, on the writing table, or by the bunk or bedside. Soldiers, prisoners, family members hold photographs, stand next to photographs, juxtapose themselves with photographs as the next best thing to their absent loved one. With light, chemicals, and paper, people held together what warring nations, economic migration, and sickness threatened to pull apart forever.

William A. Christian, Jr.

Sponsored by: