Sylvia Plachy – When Will It Be Tomorrow

Curator: Gabriella CSIZEK

Open to the public:

February 15 – May 17, 2015

on Weekdays: 14.00 - 19.00

at Weekends 11.00 - 19.00

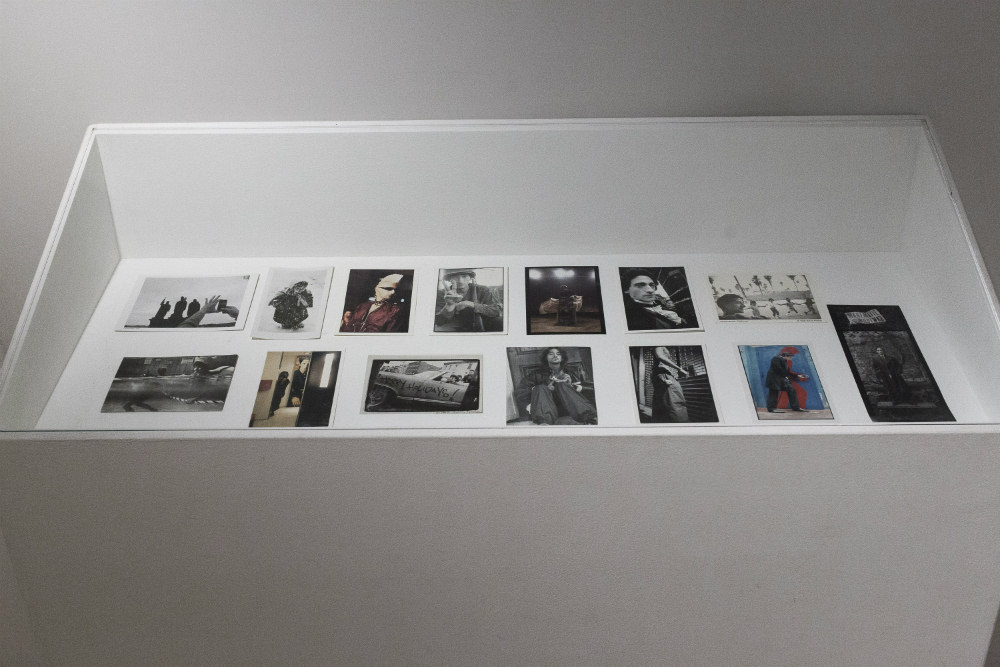

Mai Manó House is proud to present Sylvia Plachy’s exhibition When Will It Be Tomorrow. The unique exhibition of 110 images provides an overview of the photographer’s diverse oeuvre and her travels around the world. This particular selection by the photographer and the curator, Gabriella Csizek, is now displayed for the first time and leaves for other prestigious exhibition venues in Europe from here.

The exhibition’s title echoes a sentence from the artist’s childhood: this was a question she asked from her mother before going to bed at night.

The exhibited works were attracted to each other like a magnet by the title’s question. The hanging adheres to poetry rather than to some kind of intellectual logic. The sequence of images created through associations, emotions, and meanings are sometimes painful and eternally lonely, at other times they put a smile on our faces.

Some of the works have never appeared in any book or have been exhibited before in Europe. A short film by Adrien Brody about his mother is projected as part of the exhibit, while a 10-minute film portrait by Rebecca Dreyfus and Albert Maysles made in 2007 is also on view.

Sylvia Plachy is an unavoidable talent of contemporary photography. In 1956, after the revolution, the world-famous Budapest-born photographer crossed the Austrian border with her parents. Part of the way they were hidden by corn in a horse-drawn farm cart. Two years later the family settled in the New York area, where she has been living with her family since then.

She took her first photographs in the Austrian Alps at the age of 15 during a school trip with an Agfa Box camera a gift from her father. The picture was of a black goat in the snow-covered white landscape.

Gabriella Csizek curator about the exhibition

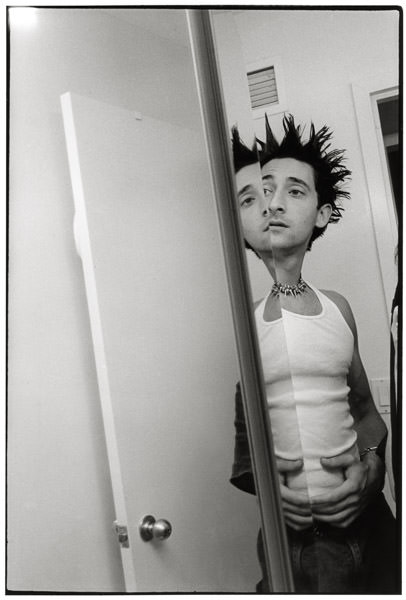

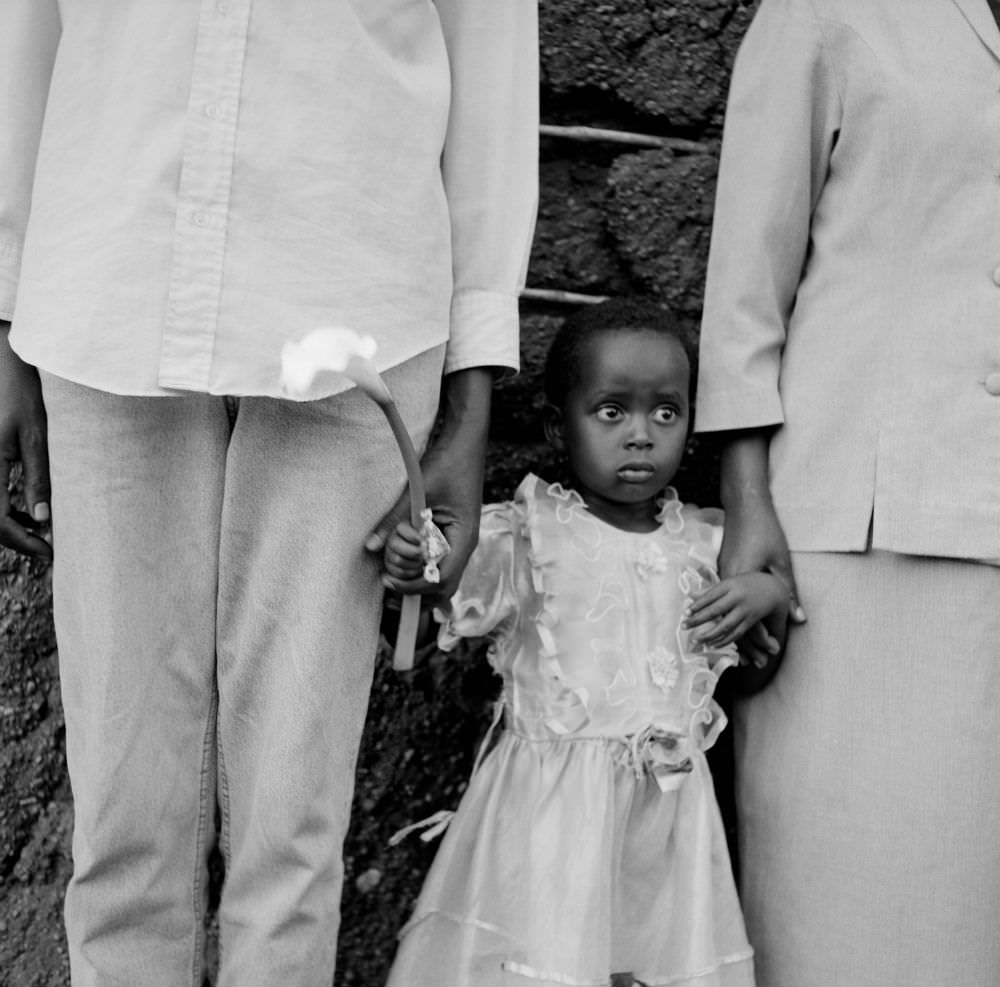

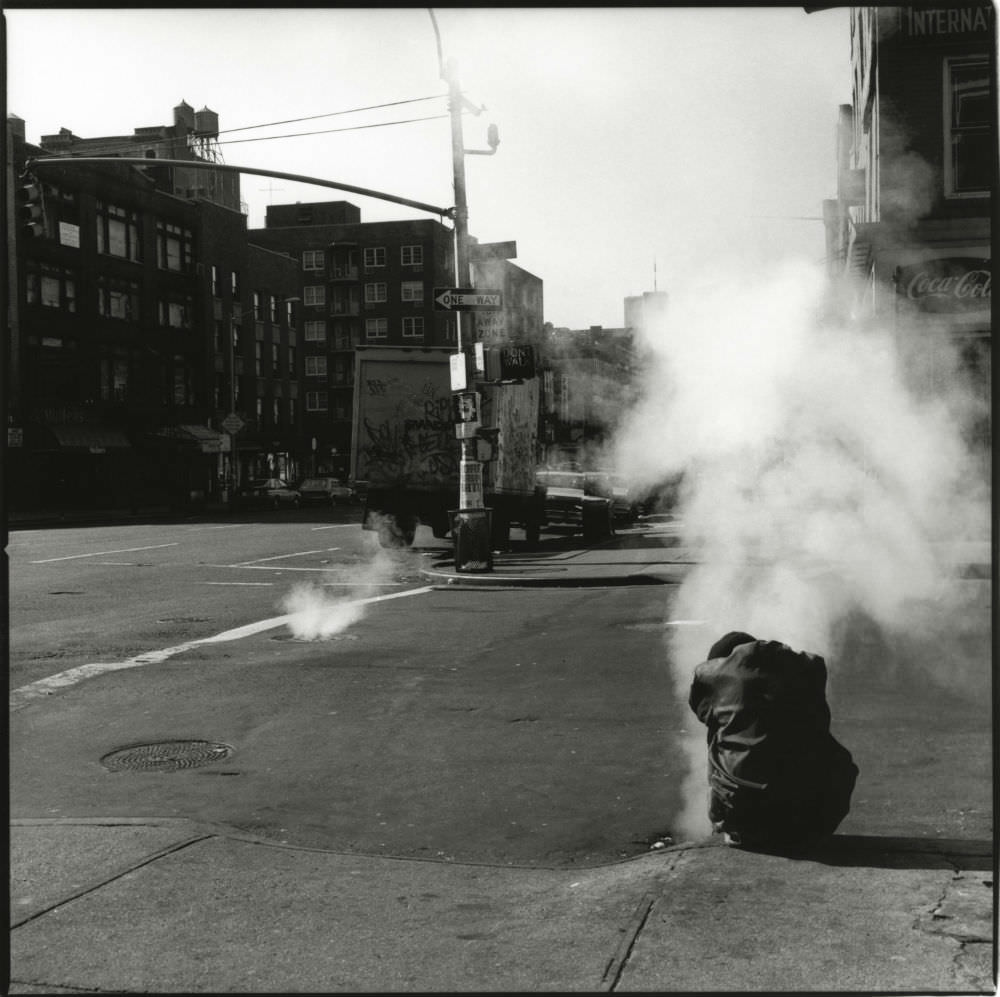

Sylvia Plachy’s humanism and commitment to truth are not in the harmonious presentation of the world or in search of its beauty; instead, she makes us see the back story with an almost imperceptible subtlety. She sees the fallibility of human existence and reveals cracks and layers of fragility in the faces or course of events. She senses the moment and converts this feeling into an image mapped onto light-sensitive paper.

She often conceals her portraits, almost displaying them as quasi-still lifes. Her subjects are never beautiful or ugly; they are people who are just who they have become and who they could be. Sylvia holds a soul-mirror in the form of a camera in her hand.

All of her images are a piece of fiction, yet genuinely real at the same time. She never finishes a story but shows it, thus giving life to the image.

Her special portraits include her photos of animals that parallel turning points in theirs and in moments of human life. Her approach lacks the notion of distance, as she does not document phenomena; she records encounters not only with people or animals but also with landscapes, spaces, and objects.

Her photographs, as if they were dreams, are rather like imprints of emotions than demonstration of facts. They tell stories without words as such.

The title of the exhibition is a sentence from her childhood she used to ask before going to bed. She intends to give this title to her next book as well.

The 110 images of the exhibition, When Will It Be Tomorrow are selected from her entire oeuvre with neither the places they were taken at, nor their theme playing a role in their inclusion, but they are chosen if they are attracted by the title’s question. The installation adheres to a logic of poetry. The individual walls are verses, bringing the halls and the exhibition as whole together into a poem, a series of poems. The sequences of images created through associations, emotions, and meanings are sometimes painful and eternally lonely. Still at times, they put a smile on our faces.

Some of the works have never appeared in any book or have been exhibited before in Europe. A short film by Adrien Brody about his mother is projected as part of the exhibit, while a 10-minute film portrait by Rebecca Dreyfus and Albert Maysles made in 2007 is also on view.

PETER RONA’S ESSAY ON SYLVIA PLACHY’S PHOTOGRAPHS

Kronos and Kairos

The ancient Greeks had two entirely different concepts for time, and these two words reflected the difference. Kronos signified the sort of time where one thing follows another. It put events in the sequential order in which they happened or are meant to happen in the future. Through a lengthy, but, on the whole, fairly linear process, kronos evolved into the secular time of our age. As Walter Benjamin noted, “homogeneous empty time”, the mark of modern consciousness, is a unit of containment that is indifferent to what fills it. It is an abstract, disciplining, schematising and distancing device that mediates experience by coercing it into a unit of account. That unit of account re-sizes experience, “puts it in perspective”, renders it as a component of schematised experience by providing it with the denominator it has in common with any other experience. Time is now an instrument to be employed in the regulation of our lives, a “resource” to be managed for the attainment of designated ends, in short, the handmaiden of the austere instrumental rationality that governs our lives today. Together with the replacement of the subjectively charged, memory laden “place” with cool, objective “space”, time becomes the thoroughly rational organiser of our lives.

Kairotic time is out of sequence time for which duration is irrelevant, when, as Hamlet puts it “the times are out of joint”, when enchantment with Creation supersedes all mediation. As Shakespeare tells us in the first scene, the entire play can be read as a meditation on kairotic time:

“Some say, that ever ‘gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated,

That bird of dawning singeth all night long:

And then, they say, no spirit can walk abroad:

The nights are wholesome, then no planets strike,

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallow’d and so gracious is the time”

Hamlet, Act l, scene l

Sylvia Plachy’s photography can be read as a rebellion against the tyranny of kronic time. It is a heroic struggle to overcome all forms of mediation in order to recapture the enchantment of direct, unmediated experience. There are no poses, and in the best of her work the subject is unaware that the photograph is being taken. This strategy runs the risk of voyeurism, but Plachy avoids this trap by eliminating the penetrating gaze – so fundamental to much of modern picture taking – from the process. There is no gaze, no posing, no premeditated composing – only the unmediated mainlining of experience, where the experience is not the witnessing of an event, but the enchantment that is born from that direct connexion between the photographer and what she sees. The subject of these pictures – as so often in great painting – is not the recording of what is seen, not even the photographer’s experience of it, but that magical connexion between the photographer and her object. They are unscheduled encounters with a truth where the truth is viscerally sensed even before its meaning is discerned. Indeed, it is that visceral moment, before the birth of its meaning, before its arrival to its settled place in our consciousness that places these pictures in kairotic time. Their subject is that “hallow’d and so gracious” time, which escaped from, has risen above and has left behind the events ordered into a sequence by kronos, so as to carry a truth that is independent of what happened before and what might happen after. The subject is not, -as in, for example, Cartier-Bresson – the encapsulation of a specific moment in specific time and space – but, rather, the denial of the specificity of kronic time. Plachy is not concerned with the capture of any “quintessential” quality, with the rendering of the “typical”, with the emblematic of any time or place, because she is not concerned with abstraction in any form. In all probability, she regards abstraction, together with any other schematic device, as a tool of abridgement.

These pictures, exuding warmth, immediacy and even charm are, in fact, deeply subversive of the instrumental rationality of our times. They speak of profound and unconditional love unbent and unaffected by anything outside of itself.

Peter Róna

Fellow

Blackfriars Hall

Oxford University